Chapter fifteen of “The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning” by Richard Mayer focuses on the Guided Discovery Learning Principle in Multimedia Learning. This principle states that people learn better when guidance is incorporated into discovery-based multimedia environments. Given the fact that education and instruction can be presented in many different ways, it is up to educators to decide which method they use in their own teaching practice. This chapter explains that “too little guidance causes the student to fail, whereas too much guidance challenges the self-directed nature of the discovery learning process” (Jong & Lazonder, 2014, p. 382). This adds credibility to the argument that guidance is beneficial throughout the learning process, however, the amount of guidance provided to achieve the best learning outcomes may depend on multiple variables.

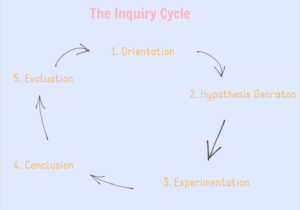

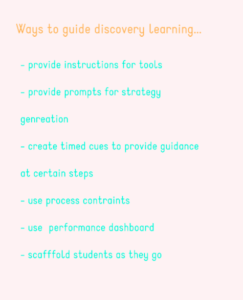

In this chapter, Ton de Jong and Ard Lazonder discuss how discovery instructional approaches result in generating deeper learning than if the information was simply given to students. Although various teaching styles can be effective under certain circumstances, Jong and Lazonder highlight the effectiveness of science education and how it “should engage students in active investigation and experimentation so as to increase and sustain their motivation” (Jong & Lazonder, 2014, p. 372). They continue to explain how unguided discovery learning is generally ineffective due to the challenges students face with the lack of direction they are given and how students will learn more if they are sufficiently guided. They then detail the different types of guidance such as process constraints, performance dashboard, prompts, heuristics, scaffolds and direct presentation of information. Process constraints “[restrict] the number of options students need to consider” (Jong & Lazonder, 2014, p. 375) in order to make the learning process more manageable. This type of guidance is best used when students lack the knowledge of how to apply the inquiry process. Once sufficient experience is gained, the constraints can be loosened. Performance dashboards give students a “real-time progress report of their discovery learning process” (Jong & Lazonder, 2014, p. 375). They help students learn about the quality of their work and are best used with students that know how to follow up on feedback. Prompts remind students of certain tasks to be completed throughout their learning process and are given to students who may not be able to complete tasks independently. More detailed prompts have proven to be more effective than less detailed prompts. Heuristics provide students with suggestions (that are even more detailed than prompts) for how to go about conducting their learning process. They are best used when students are unsure about when or how to conduct the actions necessary to carry out their learning process. Scaffolds help guide students by supplying them with “components of the process and thus structure the process” (Jong & Lazonder, 2014, p. 377). They are best used when the learning process is too challenging for students. Lastly, direct presentation of information can be given throughout the learning process and is most effective when students are unable to individually find information or their prior knowledge is limited. This allows students to explore information deeper in the discovery environment. Jong and Lazonder emphasize how studies have proven guided discovery learning to be more effective than direct instruction and unguided instruction. They also state the importance of giving the suitable amount of guidance to students. This depends on a student’s knowledge and skills and is something that needs to be monitored in order to support their evolving needs. The authors conclude this chapter by stating how further “research should focus on the design of well-balanced learning environments that, if applicable, combine different types of guidance at different levels of specificity” (Jong & Lazonder, 2014, p. 385) and how the creation of these environments will help to encourage the use of scientific discovery learning in classrooms.

The authors prove that there are many advantages when guided discovery principles are implemented into multimedia learning throughout chapter fifteen of “The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning.” The question still stands, however, should we combine different methods of guidance together? Jong and Lazonder’s chapter concluded conflicting findings. Through one study, implementing a variety of methods was found to enhance the learning outcomes of students; on the other hand, another study found it was extremely detrimental to the students’ learning. Mayer acknowledges in his paper the possibility of the negative findings being related to the two methods, self regulated scaffolding and integrated data interpretation, conflicting throughout the inquiry process; Jong and Lazonder’s findings may also have been related to the students they studied. For example, students with attention deficit disorders may struggle to stay focused when too many supports are working simultaneously. In comparison, some students who struggle to grasp concepts and processes in a singular topic may thrive off additional support. Perhaps, to better understand the consequences and successes of using a variety of methods, we first need to better understand which methods work well together, and when. By researching which methods are successful when used simultaneously, we can better equip our students for success instead of overwhelming them with conflicting methods. Whether teachers conducting inquiry based learning choose to use multiple guided discovery principles or few principles, it is important when planning to keep this in mind, “you (the student) don’t get used to the teacher giving you the answer, you get to find the answer by yourself” (Baldock and Murphrey, p. 240, 2020). This quote defines the fun students find throughout this style of learning. In their article, “Secondary Students’ Perceptions of Inquiry-based Learning in the Agriculture Classroom”, Balock and Murphrey quote a student who believes inquiry based and guided discovery learning “allows everyone to learn the same thing, but in different ways” (p. 240, 2020). These students who find joy and engagement from this teaching style prove to teachers the importance of stepping back from the methods and theories to focus on creating a lesson which allows the students to inquire and discover then implementing methods in afterward which will work to support the students on their journey.

The guided discovery principle in multimedia learning is an approach that will positively impact each student’s learning. This method incorporates various levels of guidance into discovery based situations and allows students to learn information deeply. This chapter makes it evident that in order for students to learn information effectively, they need to be engaged in their learning process. The guided discovery method allows for this as it enables educators to provide their students with various types/degrees of guidance depending on their specific learning needs. Using this method in the future will benefit each child. Being aware of various methods available and trying various methods for different students allows this method to incorporate the universal design for learning and allow deep learning. Using these methods independently as well as incorporating various strategies together will prove to be beneficial in our future teaching careers. This method is adaptable for each student and can therefore lead to deep thinking, learning and individualized success for each learner because “people learn better when guidance is incorporated into discovery-based multimedia environments” (Mayer, 2014, p.7).

References

Baldock, K., & Pesl Murphrey, T. (2020). Secondary Students’ Perceptions of Inquiry-based Learning in the Agriculture Classroom. Journal of Agricultural Education

De Jong, T., & Lazonder, A. (2014). The Guided Discovery Learning Principle in Multimedia Learning. In R. Mayer (Ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology, pp. 371-390). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139547369.019

Mayer, R. E. (Ed.). (2014). The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139547369

Pwalshy. (2019, March 25). Discovery Learning – Bruner [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e1MTybVmF5Y

Schwartz, A. (2017, June 5). CI149 – Guided Discovery Model. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Nm2Uz7bELsw